It’s been several years since I’ve posted anything here, but I recently had occasion to retell an abbreviated version of this story to a friend, and I decided I would repost the full story here as well.

When I was in college I went on a hiking trip in underground limestone caves in upstate New York. Cell phones don’t work underground, and it was so wet that all electronics that weren’t waterproof had to be left behind. We used head lamps that were powered by calcium carbide, or what’s just called carbide, which is a mineral that when mixed with water produces flammable acetylene gas, and burns brightly against a reflector when ignited. It has a flint igniter similar to a Bic lighter. You bring a bag of carbide rocks along and you’ve got a light whose batteries won’t run down when you need it most. It needs only water and gravity to work.

When I was in college I went on a hiking trip in underground limestone caves in upstate New York. Cell phones don’t work underground, and it was so wet that all electronics that weren’t waterproof had to be left behind. We used head lamps that were powered by calcium carbide, or what’s just called carbide, which is a mineral that when mixed with water produces flammable acetylene gas, and burns brightly against a reflector when ignited. It has a flint igniter similar to a Bic lighter. You bring a bag of carbide rocks along and you’ve got a light whose batteries won’t run down when you need it most. It needs only water and gravity to work.

We brought some friends from McGill University and it was a total of about 10 people. It was NOT a public tourist attraction. Getting to it involved driving to a large farm in the middle of nowhere in Schoharie County, asking the owner’s permission, getting yourself rigged up and rappelling down a couple hundred feet through a small hole in the ground covered only by an iron sewer drain cover.

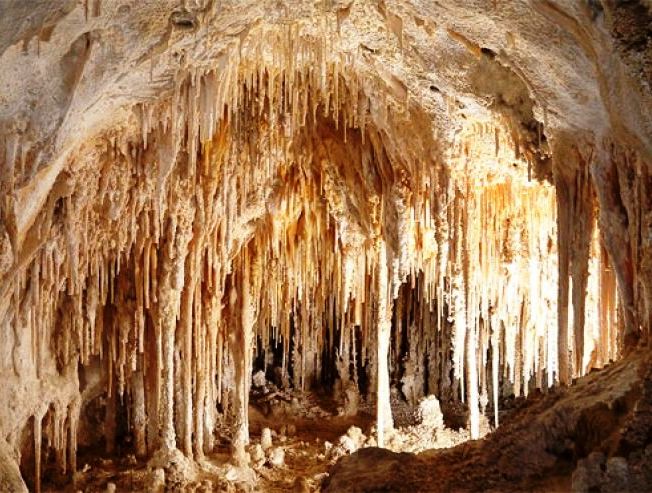

Once down to the bottom, we worked our way through rocky passages for a couple hundred yards that were narrow enough to stop someone who didn’t skip dessert that day, and then into a massive cavern with hundreds of sleeping bats hanging from the ceiling. Well, not all of them were sleeping. A dozen or so were flying around, and the ones that were sleeping could wake up from a tiny rise in temperature – so it wasn’t wise to get too close to them. After resting there and taking it all in for a bit, the senior spelunkers pointed to the next phase of the journey, a small opening at the far side of the cavern through which a small stream flowed. At the other side, they said, was a beautiful crystalline waterfall composed of stalactite formations that were millions of years in the making.

The opening was only about two feet high, so you had to crawl on hands and knees in the streambed to get there. Since we were using those carbide-powered head lights mounted to spelunking helmets, you had to hold your head up or your light would go out. This was no small challenge.

The opening was only about two feet high, so you had to crawl on hands and knees in the streambed to get there. Since we were using those carbide-powered head lights mounted to spelunking helmets, you had to hold your head up or your light would go out. This was no small challenge.

They said it was about 400 yards away and was a tough crawl, and recommended only those who were brave and strong enough attempt it. Since they’d already done it, they stayed back and two teams of us decided to attempt it.

I led the first team of four of us and began the arduous crawl down the streambed into the cave-within-a-cave. At times the ceiling was down to no more than a foot and a half and my helmet scraped against it as I moved forward. After what must have been about 300 yards I was really cold, wet and worn out, and as I paused to regain my strength my head accidentally dipped into the stream and my light went out.

The darkness in an underground cave is the darkest dark you will ever experience on planet earth. I was a good distance ahead of the next guy behind me, and when that light went out I got to experience it first-hand. You start seeing things that aren’t there, as your brain struggles to figure out how to adapt to the complete absence of any light whatsoever. The igniter had also gotten wet and would no longer spark, so with no way to restart my carbide lamp in the cramped quarters I let the next person behind me know, and let him squeeze past to go ahead of me as we continued on.

With only the dim flicker of that light ahead of me to go by, I crawled on with the expectation of something awesome up ahead that few people had ever experienced. It better be worth it, I thought, this is hell getting there.

My crawl to paradise continued, until I heard the guy ahead of me say that the ceiling had completely closed down on him and there was nowhere else to go. It was a dead end.

And it was so cramped there was no way to turn my 6’2 frame around, either.

So, with no light, soaking wet, freezing cold, and nearly exhausted, I along with the rest of the team got to crawl back out of the passage backwards.

When we got back to the cavern the senior spelunkers were having a good laugh at our expense. “We tell all the first-timers about the crystal waterfall,” they said. “You guys always fall for it.”

The lesson is, don’t trust the senior guys, and when the ceiling’s headed for the floor, you gotta know when to bail.